Subscribe to our newsletter to find out about all the news and promotions, and automatically receive a welcome discount coupon in your email.

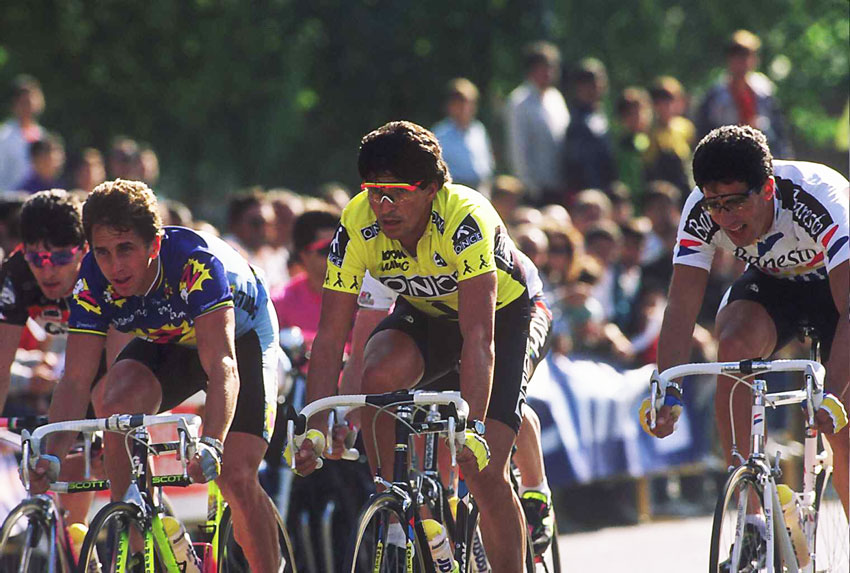

It was dawning in Luxembourg and Gianni bugno he was a defeated man. Dressed in the rainbow jersey of the world champion, his preparation to win the Tour de France had collapsed in the 65 kilometers that separated the start and finish of the first long time trial of the 1992 edition. A few days before, his team, the Gatorade, reinforced for the occasion by Laurent fignon y Peio Ruiz Cabestany, two excellent time trialists, had managed to surpass Banesto de Miguel Induráin in the team time trial and the Italian was euphoric: "This gives me morale," he said as soon as he got off the bike and saw that he was ahead of the Navarrese in 27 seconds.

That July 14, 1992, the French national holiday, Bugno's morale crawled over the cobblestones. In the time trial the day before he had been third, a more than decent place. The problem is that Induráin had taken a 3'41 ”advantage, a completely unexpected, historical, unrepeatable difference. "Induráin has won the Tour," Gianni said to anyone who wanted to listen to him, crestfallen, elusive.

The following year, the team that had brought him to Fignon preferred to bring him a psychologist. It didn't do much good. Lac de Madine arrived and Miguel Induráin returned to sentence the French round. Forges, in a brilliant cartoon, it showed the face of a decomposed man, with electrified hairs and a disheveled face with a headline that read: "Bugno's psychologist's psychologist." It was his sanbenito: the peak moment arrived and he would collapse. That was not entirely fair to a man whose expectations had simply been exceeded: he won the Giro too young, Alpe D´Huez won too young, he was world champion too young… How could we not ask him to win everything?

Because it just wasn't possible. the good of Luis Ocaña On Antena 3 Radio, he marveled at Gianni's pose in each escape, in each time trial: "It seems that he did not move on the bike," he said, and it was true. When Bugno, the great Bugno, rolled, it gave the feeling that someone was moving the landscape at full speed, a succession of families, trees, excited young people and caravans that passed by blurred while the transalpine squared off on the bike and did not move a single muscle.

Bugno was elegance just as Chiappucci was bravery, but Induráin was a hammer, a force of nature against which it was impossible to fight on equal terms. Outside pressure got the better of him on too many occasions, but he still won and won a lot. Maybe not as much as fans they waited - "Gianni, facci sognare", the walls of the Italian Alps used to say when the Tour passed near Sestrières - but that was not their problem but that of the fans themselves.

Gianni was doing enough with getting around a divorce, unconscionable demands, and the horrible feeling that, whatever he won, every failure on the Tour eclipsed the rest of a wonderful career.

The years of young promise

Gianni Bugno was born in Brugg, a Swiss town near the border with Italy, in February 1964. In principle, these data are usually quite accessory, but from his Swiss origin we can infer the coldness with which he would develop his professional career and his year His birth was not just any other year, but the same year that Miguel Induráin would be born, Raul Alcala o Erik breukink. Claudio Chiappucci, always restless, he had been born just a year before.

It was therefore part of one of the most talented and most caring generations in the history of cycling, the call to succeed the The world, Thin, Roche, Fignon ... born in the late 50s and who had shared Tours since the withdrawal of Bernard Hinault in 1986. In his early days, Bugno stood out as a powerful rider, a skilled time trialist and a specialist in one-day races or rounds of few stages in which he moved easily in the middle mountains.

Although Alcalá or Breukink were runners of immediate maturity, who before the age of 25 were already flirting with podiums in grand laps, Bugno, like Induráin or Chiappucci, waited for their moment without any pressure. At the age of 22, he began to win small races in Italy, even finishing his first Giro in 41st place in the standings, a not inconsiderable position for a rookie, although no one forgets that those Giros, prepared for the Moser o Visentini on the other hand, they had a limited demand and they used to decide on time trials and specific escapes, nothing to do with the orgies for climbers that the organizers prepare since the Italian-type runner feels more comfortable uphill.

His presentation in society would arrive in 1988, when he prevailed on a flat stage of the Tour de France, the same Tour that Perico Delgado would win with Induráin as one of his squires. Bugno, recently signed by the Swiss team Chateau D'Ax, in which he would spend practically his entire career with different names, caught the good escape of that day together with Jan Nevens. The stage ended in Limoges after going through a few mountain passes and the Reynolds guys were delighted that someone was going ahead. Nevens was the favorite, of course, but the lost-looking Italian surprised him with an electric sprint after 18 stages and a few kilometers of escape. Bugno, lost in the general classification, managed to climb the podium of a large one for the first time to receive the timid kisses of the Credit Lyonnais hostesses. It would not be the last.

With the pedigree that such a victory gave, Bugno continued to improve slowly but surely. In 1989 he won his first stage in the Giro, also taking advantage of one of the last stages, and finished in 23rd position almost without realizing it. It was the Giro in which Fignon swept away all his rivals and Lemond felt like a cyclist again after two years missing due to a hunting accident. The duel between the French and the American was repeated that year on the Tour with the famous outcome of the Paris time trial where Lemond would deprive Fignon of his third win by just 8 seconds.

That Tour was the one that marked a before and after in the trajectory of two key men to understand the following years: Miguel Induráin was still a kid from the north with very good time trial results, winner of the Paris-Nice and number two for Pedro Delgado . Miguelón, as they still called him, won in Cauterets, Pyrenean stage in which Perico wanted to set up a scabechina and only partially succeeded. Gianni Bugno had never cared about making a good general, it was something that came out of talent, but in 1989, it was no longer so easy to get him off the hook: in the first time he was among the top ten, he knew how to sneak into the right leaks and resisted on the mountain long enough to touch the top 10 for the first time in his career, finishing eighth at his fetish summit, Alpe D´Huez.

In the end he was eleventh, more than 20 minutes behind Lemond, but almost 10 ahead of Induráin. There was something more than a classic maniac there, he just needed to believe it.

The Giro of 1990

At the age of 26 and after winning the demanding Milan-San Remo, Gianni Bugno appeared at the start of the Giro d'Italia as one of the candidates for animator of the race, perhaps still a step behind Fignon, Mottet, Giupponi o giovanetti, who had just won the Tour of Spain against Perico Delgado in a display of resistance. The first stage was the usual short time trial with the name of Thierry marie, just 13 kilometers ideal for showcasing the prologues.

Bugno came out relaxed, aware that it was good to start among the first and by the end of the afternoon it turned out that he had taken the stage and the pink jersey. It could be understood as a relative surprise because yes, the boy climbed and rolled well, but beating Marie in those days were big words. Without a defined leader, the Chateau D'Ax decided to defend the jersey until its wearer fainted, sooner rather than later, or simply some breakaway broke the classification.

The third stage ended at the mythical Vesuvius. It was the moment chosen by the Castorama to place Marie as the leader and raise Fignon in the general, but the ONCE went ahead with Edward Chozas and dynamited the group of favorites: Bugno still had time to demarcate in the last kilometer and take a few seconds out of the ugrumov, lejarreta and company. In the general classification, the Swiss-Italian remained in the lead with 43 ”of advantage over the aforementioned Chozas and more than a minute over Laurent Fignon. Just four days later, in Vallombrosa, he was taking his second stage, this time in the mountains, while his rivals exploded: not only Chozas, but also Fignon and Lemond.

Bugno was beginning to be the idol with light eyes. Elegant, like a good Italian, capable of attacking in pink, remembering the eternal Fausto Coppi ... he hit the great ax of that Giro in the 68-kilometer Cuneo time trial. Although he could only be second, he reinforced his leadership to the point of leaving his most immediate pursuer, Marco Giovanni, more than four minutes. There were nine stages left and fainting was possible but unlikely. Bugno began to cherish the possibility of winning the Giro being a leader from the first to the last stage, something they had only achieved in the past girardengo in 1919, binda The 1923 y Eddy Merckx in 1973, the year that "El Caníbal" decided to put aside the Tour to focus on Giro y Vuelta.

Bugno's dominance was equivalent to that of the Belgian in his best days, although it is true that his rivals were not impressive. In the Pordoi ran away with Charly Mottet, put another two minutes to the rest of the peloton and gave him the stage victory, in the Mortirolo he endured the attacks without problems and finished the Giro winning the last time trial with overwhelming authority, beating Marino Lejarreta in almost a minute and a half and leaving to Mottet, second in the final general, at 6'33 ”, an exaggerated difference. Giupponi's squire in the Carrera team, a certain Claudio Chiappucci, would end up in fourth position of that final time-trial, called to glory a few weeks later.

And is that the 1990 Tour It was the Chiappucci Tour, although Lemond won it and it is possible that Bugno did not like that too much because by then it was already clear that he was a much better rider than the Varesino. What remained to be seen is whether he had his guts. Chiappucci launched into a suicidal escape in the second stage and remained in the lead until the last time trial in which he gave up with all the honor in the world.

Chiappucci's display, his determination, that way of attacking everywhere to get seconds that could help him hold the lead when Lemond started, his rogue Italian physique and his constant expressiveness left a more than acceptable Tour of the runner in the background of the Chateau D'Ax, already under the name of Gatorade, who, far from accusing the effort of the recently finished Giro, won two stages - Alpe D'Huez and Bordeaux - and finished the French round in a creditable seventh place, just ahead of Alcalá and Induráin.

The change had already arrived: Lemond and Delgado may have had one more Tour on their legs, but the Generation of '64 - including Chiappucci - was ready to take command of international cycling. To confirm his star status, Bugno was a bronze medalist in the World Road Championships, he would win the World Cup, which rewarded the best classified in the most important classics, and he would finish the year as number one in the UCI Ranking.

The future was his. It could not be otherwise.

Tours with Induráin and Chiappucci

Bugno's career may have been marked by the descent of the Tourmalet on the thirteenth stage of the 1991 Tour. We'll never know, but it's good to start this part of the story right then: the group of favorites squirms their way to the top of the hill. Pyrenean colossus. Delgado loses ten minutes and says goodbye to the Tour, Breukink, Kelly, Alcalá and the entire PDM team had withdrawn days before due to a strange virus, the surprising leader Leblanc lost his rope but struggled to rejoin. France vibrates with her young idol. The heat is unbearable and Luc is losing meters while the camera fixed on the top shows us that Lemond is also beginning to drop, with his jersey open, without airand in the lungs.

His first fainting in three years.

It is the moment of the brave, of those who have spent the entire Tour waiting for this moment, in a tense calm that caused criticism to rain on the youngsters. So they wanted to win the Tour, without leaving the site? Induráin went to the top of the group and while the others gathered food and newspapers he threw himself into the open grave to leave the American behind. At once he realized that he had gone alone. Nobody reacted. While the group of favorites, with Mottet, hampstenAs Fignon and company were getting organized, Claudio Chiappucci decided to join the party.

In a seen and unseen, the coulotte of Career he disappeared from sight and Bugno was still there, watching, as if thinking: "Where are these going with what's left and how hot it is?", hoping that the weather and the road would put everyone in their place. It was not so. Induráin waited for Chiappucci and together they made their way to Val Louron. By the time Bugno realized his mistake and went after them, it was too late: he had given up a minute and a half in the key stage and was in third place overall, 10 ”behind Mottet, three minutes more than the new one. leader, Miguel Induráin.

For the experts, the thing was clear: the Tour was a matter of two unless Chiappucci returned to throw the blanket around his head. Banesto, who had built a luxury team for their two stars, dominated the race with skill: at Gap, they kept Lemond's escape under control, at Alpe D´Huez they left Induráin as high as possible, with an exhibition of Jean-François Bernard. For the second year in a row, Bugno, with his Italian champion jersey obtained days before, triumphed in the most charismatic goal of contemporary cycling and he rose to second place in the general ... but he only started a second from Induráin.

There was less and less left and Spain vibrated to the rhythm of the great Pedro González and the “Apache” of the Shadows.

Bugno tried it at the Joux-Plagne, on the way to Morzine, but Delgado and Rondon they stopped him in his tracks. The Italian reached the final time trial 3'09 ”behind the leader. Chiappucci was marching almost five minutes away. Against another rival, perhaps the miracle would have been possible, but not against the Navarrese, who not only kept the lead but also won the last time trial as he had won the first, but with even more margin. Bugno finished second, just under half a minute away.

That duel promised to last several years, but, strictly speaking, it only lasted one more. In 1992, Induráin came to the Tour as champion of the Giro d'Italia, a Giro that Bugno had given up to better prepare for the French race, which earned him a lot of criticism in his country and put added pressure on him: he couldn't defraud. In the year that had passed since his "distraction" from the Tourmalet, the Italian had won the World Championship on the road, the Classic of San Sebastián and a stage of the Tour of Switzerland. The Gatorade presented a spectacular team, with Laurent Fignon as a luxury domestique, Abelardo Rondón, signed by Banesto himself, and Cabestany fulfilling his last services.

However, as stated at the beginning of the report, the excitement lasted exactly nine stages, which took Induráin to show himself in Luxembourg and distance Bugno by almost four minutes. Why did it fall apart like that? Impossible to know. There was more than half a Tour left, he was world champion, he had reserved the whole year for that moment ... and at the first change he came out melancholy to admit his defeat. The rest of the Tour was a kind of torture, as if he was running forced, forced, with his mind elsewhere. Not only did he miss Induráin, but he let Chiappucci pass him. "El Diablo" Chiappucci with his endearing "tifoso" with a black beard at the time and a trident in hand that accompanied him up the slopes and even today he is still there confirming that once one begins to make a fool of himself on TV, it is very complicated stop.

Chiappucci was the only one who put Induráin on the ropes, with his unlikely escape heading to Sestrières, that had Banesto shooting all day and that caused a major bird of Navarre just when it seemed that he was going to reach him in the final ascent. Bug could not have taken advantage of the circumstance, but by then he was completely broken. He had gone after Chiappucci at the wrong time, always gabled. In Alpe D´Huez he left nine minutes and if he got the final podium in Paris, a third place that didn't taste like anything - "I've already been second, what is the use of being third?", He said midway through the race - It was for his excellent final time trial, just 40 ”behind Emperor Induráin.

If that meant any kind of hope for the following year, 1993, the year of the psychologist and Lac de Madine, Bugno himself was soon in charge of ending it. He appeared crestfallen and left crestfallen: in the middle, a lot of disappointments that took him to 20th place overall after having been 18th in the Giro. The time of the grand tours was running out before even turning 30 years old. He would win single stages but would never be in the elite of a Tour again: in 1994 he retired and in 1995 he finished outside the top 50. It was his last participation.

Champion of Italy, champion of the world

It is unfair to value Bugno for his second places and his disabilities. Gianni was an outstanding figure without the persistence necessary to endure three weeks of relentless heat in France. He won the Giro the year he was due to win it and built an excellent track record based on one-day races and small laps, the scenario in which he felt most comfortable, combining his enormous talent with great intelligence when reading the competition.

He won the Giro de los Apennines, a minor competition, during his first three years as a professional; The year of his explosion in the Giro d'Italia, he had already won the Milan-San Remo and would do the same with the Tour de Romandie, a race at that time of great prestige. In 1991, apart from being second in the Tour de France, he won the National Championship, with the corresponding green, white and red jersey, and finished the season by beating Steven Rooks and Miguel Indurain in the Road World Championship held in Stuttgart.

The World Cup has always been a first-rate race for Italians. To give an example, the first Spanish rider to win a World Cup was abraham olano, in 1995. Before Freire, up to eleven different Italians had already won the title: the legendary binda, War, coppi, Baldini, adorni, Low, gimondi, saroni, Argentine, fondryest and Bugno himself. Every year there are fights to see who runs the team, who works for whom; fighting the egos of your classicists is a titanic task ...

To this we must add that in Italy, at the beginning of the decade, there was enormous competition: Moustache y Cipollini they dominated the sprints; Argentin, Bontempi, and Fondriest still held on like rollers of fortune ... and Chioccioli, Giovanetti, Franco Vona or Chiappucci had shown their background by winning or standing out in great laps. To what extent did working as a bloc make sense for Bugno, a man used to collapsing at the decisive moment?

Italy has a tradition of sports debates even greater than the Spanish: Coppi o bartalic, Rivera o Mazzola, Accounts o Red… and so on to Chiappucci or Bugno. Claudio represented the most Latin Italian: the brawler who attacked the aid stations, on the descents, who launched himself into the adventure 100 kilometers from the finish line and never looked back. Bugno was a quiet, modern, elegant man, the Italy of tall, handsome, well-dressed boys, the Italy that is generally disliked even in its own country.

At times, Bugno complained of not being loved enough, of living in Chiappucci's shadow despite having a much better record. Bugno thought too much and had very little luck: his triumph in the 1991 World Cup was joined the 1992 in Benidorm, in front of Jalabert y Konychev. Those two world championships make their versatility clear: one won against a climber and a time trialist; the other, before a sprinter and a specialist in dynamiting platoons in the last kilometer.

Unfortunately, hardly anyone remembers. They remember their defeats but very little of their triumphs. With Chiappucci it happens the other way around: we remember his feats and we never stop to think if he was wasting a lot or a little time in the time trials. Chiappucci was brave and that put everything in the background. Bugno calculated and there is nothing that a Mediterranean hates as much as a man who calculates.

Caffeine doping

After his failures in Tours of '91, '92 and '93, failures, as we have said, highly nuanced because he won several stages and got two podiums, Bugno found himself with the biggest stick of his career: a positive for caffeine during the Agostoni Cup. , held on August 17, 1994. Gianni was still a very good runner, even though everyone gave him a break because baiting him seemed surprisingly easy. That same year, he had won a stage of the Giro d'Italia, in which he was especially active although very far in the general of the berzin, pantani, Induráin and company, and had imposed in the prestigious Tour of Flanders, a test for the chosen ones.

His presence on the Tour did not last long, as he had to abandon, and was already in the middle of preparing for the World Championship, his fetish career, when the news of the positive appeared: 16,8 micograms where only 12 were accepted. Of course, the The runner denied any doping, but his career ended with a two-year ban from the Italian Federation. They were other times: the fight against doping did not have the resources that it has now and there were not cases as grotesque as the 2002 Tour, where lance Armstrong —With an open cause for systematic doping— he was followed Joseba Beloki, Raimundas Rumsas y Santiago Botero, all three sanctioned at some point in their careers for continued cheating.

Bugno, who had finally formalized his divorce and started a new relationship, fought as best he could with somewhat strange arguments: “I drink a lot of coffee"," It was very hot those days and I also had tea "... We will never know how much truth there was in those excuses, in fact, years later, Bugno's name appeared next to that of tonkov in an investigation for the use of EPO in the nineties, although the thing did not go further since the broker was retired. The enigma of the cleanliness of cycling in those years remains undiscovered, we will have to limit ourselves to trusting our idols.

The fact is that Bugno's arguments convinced his Federation in part: they maintained the positive but applied the UCI regulation, which at that time punished excess caffeine with a three-month penalty. Since the only race to play was the World Cup and Gianni had ankle discomfort and had discarded himself, it can be said that that episode had no effect on his sports career beyond the shadow of a doubt. "My name has been stained," said the Italian, very dignified. And I would like to believe you, because I have rarely seen someone with such style on a bicycle, but it is inevitable to remind them of those same words. Virenque, pantani, Heras, ullrich, the entire Festina team ...

With the doping episode now forgotten and the enthusiasm of a new sentimental life, Bugno reoriented his role in the peloton by considering more modest goals that would make him enjoy cycling and not live in continuous dissatisfaction. It must be horrible to know that every day you are disappointing someone. When nobody expected anything from Bugno, a veteran with a thousand resources arrived. He left Polti, where he had raced in 1994 after six seasons of loyalty to Chateau D'Ax-Gatorade, and went to MG, a team in which his riding skills were valued and in which no one asked him for any feat of three weeks. Later, the team merged with Mapei, where Bugno would run his last two seasons.

In 1995, already 31 years old, and while Induráin won his fifth consecutive Tour, the Italian took the Tour of the Mediterranean, won the Italian Championship again With the corresponding national jersey that he proudly wore in what would be his last Tour de France, and won the Agostoni Cup, where he tested positive a year ago. This time it is known that it was not hot enough to drink tea and also Bugno fulfilled the unusual promise made before the judges of his case: "I will not drink coffee again."

The following season was not bad either: Bugno was very comfortable in anonymity and each victory of his was celebrated as it had not been celebrated when he really needed it. He caught a stage in the Giro del Trentino, another in the Giro d'Italia (the ninth of his career), he excelled in the Tour of Switzerland with another partial victory and celebrated his first participation in the Tour of Spain taking the stage that ended in the DYC Distilleries, that goal that elevated Perico Delgado in 1985, when he stole the Vuelta a España from the Scotsman Robert Miller.

The victory was a true exhibition, riding alone, in a block, in the last kilometers, in front of a group of favorites hungry for victory. The advantage started for 10 seconds, went up to 13, then 20… He left behind julich, in the group they waited Rominger, Axel Merckx or Chava Jimenez, but there was no way: Bugno kept the pace and only trusted in the final stretch, with the Spaniards, who deep down we admired him so much, cheering him on, and Rominger sprinting behind, at 35, to get bonus seconds.

Gianni's love affair with Spain would last two more years. The truth is that, except for very minor tests, Bugno had disappeared from the squad. Induráin was retired, like Breukink and Alcalá, Chiappucci was dragging himself in second-row teams and Jan Ullrich was vying with Marco Pantani for world supremacy. In these, Bugno planted himself in the Vuelta a España in 1998, on the brink of retreat, with the idea of helping the cyclothymic in whatever way he could. vandenbroucke, and did not want to leave empty.

It was the great Return of Chava Jiménez, the one in which he won four mountain stages and wore yellow until the last day, which gave up against the clock against abraham olano y Fernando Escartin. Bugno was 34 years old and did not count for anyone. His Vuelta was being as bland as the rest of the season, but on the way to Jaca snuck on an eleven-man getaway that was reduced as it advanced a stinking terrain, of constant ascents and descents, for sufferers.

With 25 kilometers to go, there were only four men ahead: Sgambelluri, Uriarte y Santi White, the eternal promise of the Spanish cycling of the 90s. Bugno attacked with a dry demarraje that nobody could follow and from there he put the calculator back into operation. As if this were the Giro del 90, Gianni advanced and advanced on his way to the finish line and finished with an advantage of almost two minutes over Blanco, second that day. He knew it was the end and it was still a beautiful ending, arms raised again, twelve years as a professional without ever stopping winning.

All to be remembered as an illustrious loser.

That winter he hung up his bike and dedicated himself to living away from the spotlight, like a liberated kid. He devoted himself to his passion for helicopters and earned his rescue pilot's license. In 2008 he was even encouraged to take the race helicopter to the Giro d'Italia. It is the closest to a bicycle that we have seen him again. Now how Romario, is dedicated to politics. The extremes, sooner or later, touch.

Other entries that they may interest you.

42K · All rights reserved

Comments

Post a first comment for this entry!